MJ Chevesich, Graduate Research Assistant

This post was originally going to be all about intersectionality, theory, and relationship sexual violence (RSV), but the more conversations I had with coworkers and family members about RSV and my role in the MCVP, I realized that before we can even talk about the complexities of identity and oppression, we first need to shift our thinking about who we center in conversations about RSV.

I recently attended a presentation for my graduate management course in the Division of Public Health. The management scenario to work through was about how a clinic manager should handle one of their employees coming to them who was experiencing RSV. In the scenario, “Nancy” recently broke up with a controlling partner who then snuck into her car to leave a note saying “without you, it’s over” with a bullet next to it on her dash. Now, the whole point of this scenario was to place yourself in the clinic manager role. The point of the scenario was not RSV itself, RSV was just a placeholder for a difficult conversation in a managerial job. The “solutions” given to what to do mainly focused on hiring more security guards to walk employees to their car, giving employees pepper spray, and even looking into clinic policy around open-carry rules. The main problem in this scenario was that Nancy was experiencing a “personal” problem and that her employer could not do anything.

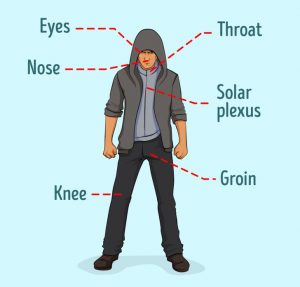

I could tell people were starting to get uncomfortable with the scenario since there was no warning that RSV and guns of all things would be discussed during a class that previously only dealt with organizational charts. The discussion quickly went into how the clinic could bring in self-defense experts to teach classes, set money aside in the budget for tasers and pepper spray, but the big elephant in the room still lingered, what would happen to Nancy when she went home? People feel uncomfortable discussing RSV for a variety of reasons, one of them being the fear of saying “the wrong thing.” One way the anxiety of saying the wrong thing in a discussion on RSV can be alleviated is by setting discussion norms, boundaries and by creating a space of learning instead in which we acknowledge the complexities of the subject as well as the differences in our lived experiences. Setting class/ discussion norms aren’t usually part of the Public Health learning environment, but if they had been, people would maybe have felt more comfortable discussing a difficult topic. In addition to problem-solving how a future workplace could handle RSV, there should also be a focus on creating spaces where students and employees can feel empowered to be part of the conversation.

warning that RSV and guns of all things would be discussed during a class that previously only dealt with organizational charts. The discussion quickly went into how the clinic could bring in self-defense experts to teach classes, set money aside in the budget for tasers and pepper spray, but the big elephant in the room still lingered, what would happen to Nancy when she went home? People feel uncomfortable discussing RSV for a variety of reasons, one of them being the fear of saying “the wrong thing.” One way the anxiety of saying the wrong thing in a discussion on RSV can be alleviated is by setting discussion norms, boundaries and by creating a space of learning instead in which we acknowledge the complexities of the subject as well as the differences in our lived experiences. Setting class/ discussion norms aren’t usually part of the Public Health learning environment, but if they had been, people would maybe have felt more comfortable discussing a difficult topic. In addition to problem-solving how a future workplace could handle RSV, there should also be a focus on creating spaces where students and employees can feel empowered to be part of the conversation.

I only felt comfortable raising my hand and bringing up how we should address violence before it even happens because of my work with the MCVP. I said that we should address Nancy’s partner since, after all, we wouldn’t have to set money aside, bring in experts, and make coworkers feel responsible for one another if the original cause of potential violence was stopped. When you bring up these points, you immediately see the light bulbs go off in people’s heads. “Oh yeah, of course, that makes sense, the partner should be addressed.” However, conversations also quickly turn to “Yeah, ok, but how do we address the partner?” While I in no way claim to know all of the answers and have all of the solutions, the point is that once we start shifting our thinking from victims to perpetrators we can stop spending time and brainpower on pepper sprays and tasers and instead use clinic (or organizational) resources to answer the bigger question. I do not have all the answers, but maybe someone sitting through yet another victim-focused course might and we just need to shift their focus to one of prevention.

MJ Chevesich is a second-year graduate student in the Division of Public Health at the University of Utah and a staff member for the McCluskey Center for Violence Prevention.

MJ Chevesich is a second-year graduate student in the Division of Public Health at the University of Utah and a staff member for the McCluskey Center for Violence Prevention.