Blessing Heelis, Student Staff Member

Rates of campus sexual violence have not changed since 1957. Yes, really. This is a hard fact to swallow, especially in an age that feels progressive. The question then becomes, “how do we fix this?” Herein lies the complexity. An obvious solution is to spread awareness and create resources for victims of sexual violence. While good-intentioned and definitely a necessity, these one-size-fits-all services, policies, and institutions often ignore the nuances of sexual violence. For example, minoritized people experience sexual violence at higher, disproportionate rates to their straight, abled, cisgender white peers. This is true not just of the present-day, but throughout history. Slavery is a good case in point. Many slaveholders systematically raped their slaves or forced sexual relations between slaves to breed more workers, thereby increasing the slaveholders’ profits. Historical backdrops such as these explain patterns of perpetration today as well as residual oppression in systems of power. To this end, we attempt to employ a power-conscious framework throughout our efforts in the MCVP.

WHAT IS THE POWER-CONSCIOUS FRAMEWORK?

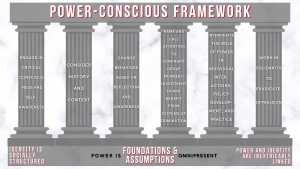

(The power-conscious framework as detailed in Sexual Violence on Campus: Power-Conscious Approaches to Awareness, Prevention, and Response)

The power-conscious framework calls attention to “the role of power in the individual, institutional, and cultural levels of interactions, policies, and practices.” In turn, a power-conscious approach will necessitate that the symptoms and causes of oppression be addressed. This is key for our work at the MCVP; like a hydra, responding to victims is only a temporary solution to sexual violence that quickly reappears and rears its ugly head once more. The complete elimination of campus sexual violence is impossible without removing the source of the oppression altogether.

The framework assumes three things: power is omnipresent, power and identity are inextricably linked, and identity is socially constructed and its meaning changes over time.

Assumption one means power exists everywhere and in everything. This can be formal (for instance, one’s position within an institution) or informal (such as one’s sexual orientation). As a result, some people possess a greater amount of power over others.

Assumption two asserts that some identities, like blackness, are associated with a level of power that is greater or less than that of other identities.

The final assumption states that the power of identity is interwoven with history’s changing values and therefore fluctuates over time.

Lastly, the power-conscious framework operates according to the following six tenets.

THE SIX TENETS OF THE POWER-CONSCIOUS FRAMEWORK

The first tenet is to engage in critical consciousness and self-awareness. This focus on self-awareness is critical for those with multiple dominant identities because systems of power have been built around and cater towards them. The benefit of being white and cisgender is just one example that applies to most situations but is especially pertinent to sexual violence. Studies have shown a definite media coverage bias favoring white women as victims of violence, meanwhile, Native American women experience the most rape and sexual assault of any ethnic group; yet how many stories do we hear about them? Consequently, it is important to be mindful of how something may be harmful or exclusive to another person or group that lacks the power to be heard.

Tenet two reminds people to overcome historicism and ponder the repercussions felt today. A relevant example is 1800s property laws in which women who had been raped could only report their assault through their husband or father because the man’s “property” had been violated; essentially, women did not own their own bodies. While seemingly archaic now, those property laws still impact the public’s perception of women, virtually giving women no autonomy up until recently.

Engaging in tenets one and two allows a person to proceed to tenet three: the application of these lessons through changed behavior. Everyone should continually raise self-awareness and learn about historical oppression and accordingly alter their behavior. Crucially, one must act with his or her best knowledge, even if that knowledge is limited. For instance, a common rape myth is that most sexual violence is committed by strangers when the reality is that the majority of perpetrators are friends, family, or other individuals the victim knows. If verbal, physical, or psychological abuse is observed between two people, one should intervene to the best of their ability regardless of the degree of abuse, the relationship between the two people, or their genders (to name but a few).

The fourth tenet calls for attention to be brought to dominant group members’ benefit and privilege from membership in systems of power. A key feature of the MCVP is its emphasis on violence prevention — this means we will be focusing on perpetrators in addition to victims of sexual violence. What are the backgrounds of perpetrators? What are the most common demographic traits of perpetrators? Who is most at risk to perpetrate? These are the kinds of questions we will attempt to answer to stop sexual violence and overturn oppressive systems of power.

Tenet five asks that people name and interrogate the role of power in actions, policies, and practices. A 2017 study found that white women were less likely to intervene when a black woman was being assaulted, leading researchers to conclude that many bystander intervention programs are ineffective due to the lack of consideration for race as a barrier. Such findings make it apparent that intersectionality creates an uneven playing field, and demands that we further analyze the connection between power and oppression.

The final tenet implores people to work in solidarity to address oppression. Oppression cannot be resolved in a day, nor solely by certain groups of people. It is paramount to include everyone, including perpetrators, to fulfill the MCVP’s objective of eliminating campus sexual violence. Overbearing gatekeepers can hinder the healing process between victims and perpetrators and ultimately generate more oppression.

WHY AND HOW WE WILL USE THE POWER-CONSCIOUS FRAMEWORK?

The work we will be doing is, to say the least, unconventional, because of our concentration on sexual violence prevention, rather than raising awareness or providing response services for victims. As aforementioned, rates of campus sexual violence have remained unchanged for generations. Clearly, the current systems, institutions, and policies in place are not working. Therefore, the ambitious goal of the MCVP is not possible without overthrowing present systems of power. This poses a challenge because oppressive systems fight to maintain the status quo and retain power. Moreover, it causes much discomfort since it requires people to hold themselves and their loved ones accountable; we must come to terms with the possibility that someone we trust, maybe a brother or close friend, may have caused harm to others, and confront them about it. That being said, a power-conscious framework is vital to the MCVP and beyond. It will challenge scholars, institutions, and educators to address issues of oppression and disparate distribution of power. Though it can feel daunting, the undertaking of the MCVP through a power-conscious lens is a feat deserving of the highest attention so we can collectively eradicate the unchanging, nationwide epidemic of campus sexual violence.

Blessing Heelis is an undergraduate student majoring in anthropology with an emphasis in archaeological science. When she’s not studying, Blessing likes to hike in her favorite place — Provo Canyon. She is so excited to be among the inaugural staff of the MCVP and feels honored to be a part of something that will make a great, positive impact on our community.

Blessing Heelis is an undergraduate student majoring in anthropology with an emphasis in archaeological science. When she’s not studying, Blessing likes to hike in her favorite place — Provo Canyon. She is so excited to be among the inaugural staff of the MCVP and feels honored to be a part of something that will make a great, positive impact on our community.